Social Policy Forum Election Statement

During this year’s General Election Campaign, social policy issues that affect our lives, from education and health to welfare, have been discussed in a technical manner. However, social policy does not depend on how much money is spent on healthcare or whether pensioners get a free bus pass. It depends on how we, as a society, see ourselves and each other, on how we define our needs and wants, and our relationship with the state.

However, today social policy is not seen as the result of the decisions of active, autonomous citizens. Rather, we are encouraged to see ourselves as passive and incapable of running our own lives and our social policy reflects this. Social policy is about changing our behaviour and telling us what we should be doing to promote our ‘wellbeing’, rather than treating us as autonomous individuals or reflecting our collective desires for new social arrangements.

Introduction

During this year’s General Election Campaign, social policy issues that affect our lives, from education and health to welfare, have been discussed in a technical manner. However, social policy does not depend on how much money is spent on healthcare or whether pensioners get a free bus pass. It depends on how we, as a society, see ourselves and each other, on how we define our needs and wants, and our relationship with the state.

However, today social policy is not seen as the result of the decisions of active, autonomous citizens. Rather, we are encouraged to see ourselves as passive and incapable of running our own lives and our social policy reflects this. Social policy is about changing our behaviour and telling us what we should be doing to promote our ‘wellbeing’, rather than treating us as autonomous individuals or reflecting our collective desires for new social arrangements.

Social Care

The overarching assumption of our care system is that every child, and even older, disabled or mentally ill adults, are at risk from abusive or predatory adults in the community. This is encapsulated by the Safeguarding Vulnerable Groups Act which requires that anybody working with children, or with ‘vulnerable adults’, to be vetted by the Criminal Records Bureau. This creates a culture of suspicion where neither professionals nor even neighbours, families, or friends can be trusted with their care. While adults who work with vulnerable groups are treated as potential abusers, adults who need support are treated as children.

We need a social care system that recognises adults as free citizens, robust and autonomous, whatever disadvantages they face, and however ‘vulnerable’; and that has a sense of perspective when it comes to child protection, recognising that Every Child is not ‘at risk’ and that not every family needs ‘support’ to bring up their own children.

Education

Schools are no longer simply places to teach children, in fact they do everything but. The underlying approach to education by policy makers has been to treat it as a tool for tackling the problems that blight society at large. Schools have been seen as tools to tackle poverty and channels for ‘early intervention’ to prevent young children from turning to crime, to tackle racism and promote safer sexual relationships (amongst many other things).

Schools are not places for social engineering and the efficacy of attempts to make them so are highly dubious. Over a decade of ‘education, education, education’ and the expansion of higher education has resulted in its opposite, an emptying out of what education means and a lowering of young people’s horizons. Neither has it prevented a decline in social mobility or the proliferation of young adults classed as NEET (i.e. not in education, employment or training). We need to regain a sense of what education is for, to teach children and young people subject knowledge. Education must be an end in itself not an excuse for promoting policy fads or controlling the behaviour of children and their families.

Health

All of the three main parties are agreed that healthcare should be more personalised, that the experience of patients should take precedence over ‘one size fits all’ provision. However, this promotion of choice does not extend to public health. The parties are committed, more than ever before, to prevent us from getting ill in the first place. In practice this means more intervention into peoples’ lifestyle choices. On the heels of the smoking ban and the anti-obesity campaigns launched by the last government, we can expect more tinkering with the price of alcohol or with the design of supermarkets and public spaces to ‘nudge’ us into making the right lifestyle choices.

We need to question a healthcare policy that treats us as competent ‘expert patients’ able to choose how our healthcare is provided, but apparently incompetent to make everyday decisions about what we eat, drink and smoke. We need to have a health service that treats people when they’re sick, and even helps us to live our lives free from ill-health for as long as possible, but not one that tells us how to behave, or claims to know what’s good for us.

Housing

Housing has long been used as a tool for social engineering, from slum clearances to Thatcher’s Property Owning Democracy. However, these interventions at least had the merit of improving many peoples’ lives, making them better off or giving them greater autonomy. By contrast, housing policy today is being used to build communities (rather than houses) and to promote ‘good behaviour’ rather than the Good Society. Whether helping social tenants to get onto the housing ladder or devolving power to local residents, the underlying aim is not high quality housing, but the creation of responsible citizens.

This needs to change. The overwhelming need now is to build more houses that meet peoples’ needs and wants regardless of tenure, or whether their behaviour is deemed anti-social or not. We need a housing policy that treats houses as bricks and mortar but leaves their occupants to decide how they want to live, and how they go about addressing the day-to-day concerns of living in their neighbourhood.

Finally

Over the coming years there are certain to be substantial cuts in health, education and welfare spending more generally. The task of reforming the welfare state, however, should not be treated as an accounting exercise, but an opportunity to reassess what the state is for. For instance, ‘welfare’ in its narrowest sense is widely understood to be failing. While we need a benefits system that helps people to live their lives as independently as possible, we don’t need one that imposes conditions on people claiming benefits, blames them for their predicament and society’s problems, or fails to provide them with the jobs they need (preferring to offer them counselling).

While there is still a role for the state in meeting peoples’ needs, we need to recognise that the definition of need has widened in recent years. When the economic troubles began, in fact long before they began, the response of government was to worry about the nation’s mental health. This view of people as essentially frail and vulnerable underpins the welfare state today, from the numbers of people on incapacity benefit to the view that it is the state’s business to ensure we live a healthy lifestyle. Our relationship with the state - the basis of our social policy - needs to be reoriented and proceed from the assumption that we are capable, responsible and rational adults able to realise our own needs, make our own decisions and run our own lives.

what's happening next

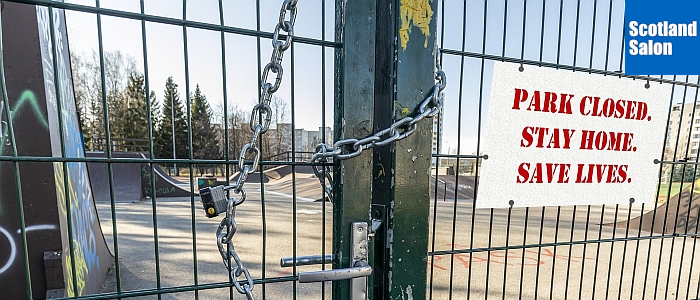

The unintended consequences of lockdown

Wednesday 2 December, 7pm, online, via Zoom